Why defence does not begin or end with a line-break

When the professional era in Rugby began in the late 1990’s, performance analysis was in its infancy. One of the main measures of the effectiveness of your defence, was simply to count the number of times the opposition broke your line when they had the ball in hand.

Although that remains a useful statistic, it is no longer the be-all and end-all of defensive measurement. What happens after a line break has been made is equally important.

One of the critical takeaways from the England tour of New Zealand back in 2014 was the All Blacks’ efficiency after the break. In the course of the first two Tests, England made as many line-breaks as New Zealand, but the Kiwis won both of the games.

Their efficiency applied both on attack and on defence, and it was one of the main differences between the two teams. They were better in support after a break had been made, and they were more intelligent when scrambling back after a break had been made against them.

That harsh lesson came back to me with full force during the Super Rugby final between the Crusaders and the Jaguares from Argentina. While the Jaguares probably created more genuine scoring chances than their opponents, the excellence of the Crusaders’ play in support and in the defensive scramble proved to be decisive.

Let’s take a look at some examples of how that advantage manifested during the game itself. The first clear scoring chance for the Jaguares occurred in the 37th minute of the match:

A fabulous offload in contact by the Jaguares’ captain Pablo Matera has released right wing Matias Moroni down the side-line with only the Crusaders full-back David Havili to beat. At least, that’s the way the situation would have looked at the start of the professional era!

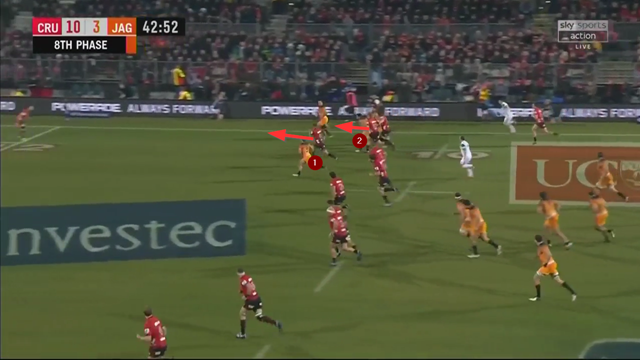

In reality, the Crusaders’ scramble defence begins to organize itself as soon as the break is made. Number 7 Matt Todd continues to chase down Moroni and outside centre Matias Orlando near touch, but the critical contribution comes from scrum-half Bryn Hall on the inside of the play:

The scrum-half is typically important as the ‘spare man’ – both in support of breaks (where he will often run a line anticipating the breach) in attack, and covering from his sweeping position behind the ruck on defence.

At the tipping point of the play in the screenshot, where the position of attackers relative to defenders decides whether a try will be scored or not, the Crusaders have all the bases covered.

Todd is within tackling distance of Orlando, and Hall has inserted himself into the space between the ball-carrier and his main support, number 15 Emiliano Boffelli. If Moroni attempts the pass inside, the chances are that Bryn Hall will intercept it.

With the support players covered, Moroni has to keep the ball and go on his own, and here Hall’s inside position proves decisive. Havili makes the tackle to stop Moroni’s momentum, and Hall closes in to force the fumble. A definite win for the scramble defence.

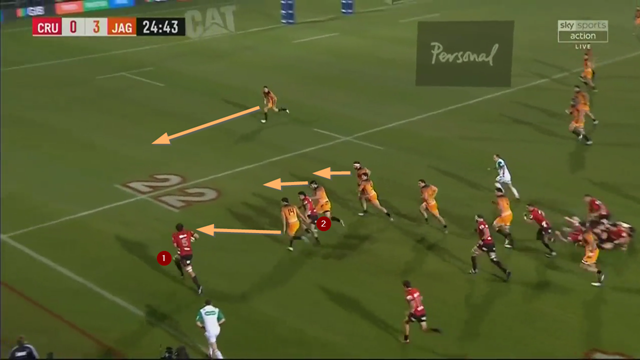

The second clear-cut scoring opportunity was created at the beginning of the second period. Again, it occurred down the right wing, and again it was a pass in contact by Matera which released the man outside him, Moroni:

Inside the ball-carrier, a classic battle for position has developed between the two 9’s, Hall and his opposite number Tomas Cubelli:

Hall has won his battle for a second time, because when Moroni looks to his left he sees that the passing route to Cubelli is blocked by the Crusaders’ half-back.

With Havili looming in front and the Jaguares’ support down the right enjoying a head-start over the Crusaders’ cover in that area, Moroni chooses to kick over the top of Havili in the hope that the situation will be the same when he regathers the ball.

In the event, it isn’t:

As Moroni goes to pass inside, he finds that the path to Orlando is now blocked by centre Braydon Ennor, while the next two players nearest the ball (Hall and number 12 Jack Goodhue) are both wearing red jerseys.

Goodhue’s persistence has to be admired. After having to turn and watch Orlando beat him to the inside support lane in the first instance, Goodhue keeps running and never gives up. After a 50-metre sprint, he is finally rewarded for his efforts. He takes the ball away from Orlando in the action of scoring and touches it down in-goal to defuse the threat.

The only try of the game was scored by the Crusaders in the 25th minute:

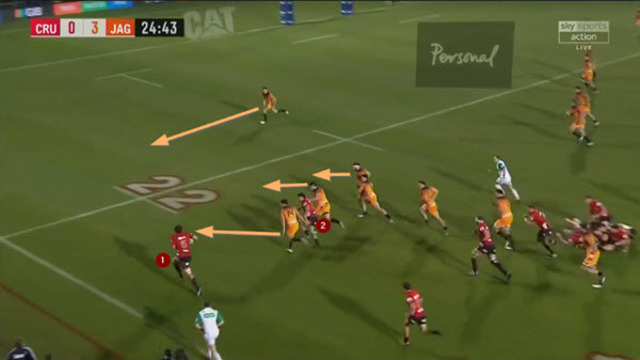

Initially the situation doesn’t look too promising for the Crusaders, with two forwards (Sam Whitelock and hooker Codie Taylor) on attack, and plenty of defensive cover coming across to the left in orange-gold jerseys:

At this stage, Boffelli will beat Whitelock to the corner flag, and Moroni is in prime position to close down the inside passing lane to Taylor. All should be well for the cover defence – or so you would think.

It is at this juncture that Whitelock and Taylor comprehensively out-manoeuvre their immediate opponents. Whitelock subtly feints to come in, then moves further away towards the touch-line, while Taylor gives Moroni an equally subtle nudge to clear the lane:

The effect is to drag both Boffelli and Moroni towards the big All Blacks’ second row, leaving Taylor just enough clear air in which to receive the in-pass and score the try. If Moroni and Boffelli had communicated better and not gone for the same man, that outcome could have been avoided.

The Super Rugby final was a powerful lesson in all of the shades and colours of defensive work – not just what to do in order to prevent a line-break from occurring, but what to do when one has just been made. The use of the spare man (the defensive scrum-half) in cover, the need to occupy the space between the ball-carrier and his principal support; and above all, for all defenders in the area never to quit on the play, are all essential elements in the construction of a successful scramble defence.