One of the biggest questions hanging over New Zealand rugby going into the World Cup was the same uncertainty which has bedevilled it ever since the departure of ‘the three wise men’ [Sir Graham Henry, Sir Steve Hansen and ‘the Professor’ Wayne Smith], and the end of a golden era of All Blacks success between 2008 and 2018.

Can a Kiwi attack handle an all-out Test-level rush defence? Towards the end of the Hansen era, the answer to that question was probably ‘No’. New Zealand drew a series with the British & Irish Lions in 2017 in which Andy Farrell’s defence only leaked five tries in the three Tests, and 16 tries in total on the 10-match tour. A meagre average of just 1.6 tries per game is not what New Zealand rugby public is used to.

The All Blacks overcame Ireland’s Farrell-coached D handily at the quarter-final stage of the 2019 World Cup but lost to an improved, John Mitchell-guided version the following week versus England. Since South Africa’s withdrawal from Super Rugby, New Zealand teams are getting less and less practice against defences which emphasize movement from out-to-in, and attacking the ball rather than watching the man.

As the ex-Crusaders defensive assistant, and Champions Cup-winning head coach of La Rochelle Ronan O’Gara explained,

“I think where teams have probably gone beyond them [the All Blacks] is on the defensive side. Their attack has always been top notch but I think defensively it seems like they are still defending the man, which nowadays, with teams’ capacity to retain the ball, is you keep pushing them towards the sideline, the opposition is going to have too much possession and be able to fire too many shots and they probably have to defend a lot of players with X-factor.”

Defences in Super Rugby do not attack the ball as consistently as their equivalents in Europe and South Africa, so New Zealand does not see those ‘hard’ shapes on D repeated often enough to develop antidotes.

In their two toughest defensive tests of the recent World Cup (against France on opening night and against South Africa on the final evening of the tournament) the All Blacks totalled three tries in two games, and France and South Africa operate the two most dominant rush defences on the planet.

Why so? In their golden decade, the All Blacks’ attack was characterized by the width it was always able to sustain. The old Canterbury/Crusaders 2-4-2 pattern split into only three forward pods, which needed to be connected by a second pass made off #10. Other attacking shapes [like the 1-3-3-1] can be linked by one pass, directly off the #9.

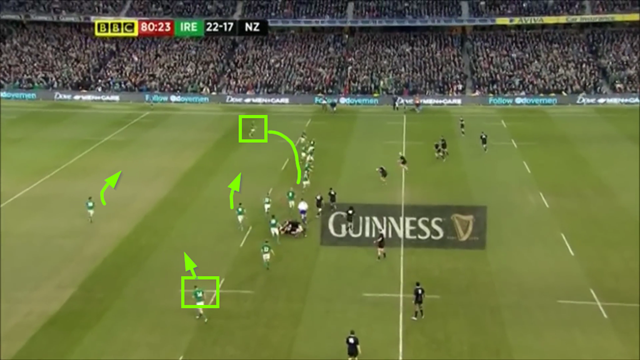

The climax of the 2013 game between Ireland and New Zealand provided a seminal model for what the All Blacks of that era could achieve, even under the greatest of pressure:

The final sequence features nine phases of two passes or more, and only three one-pass phases. It hits the two 15m corridors on four separate occasions in the process.

It is worth examining this passage of play in more detail, to set the background for just how much the game has changed for the All Blacks in attack:

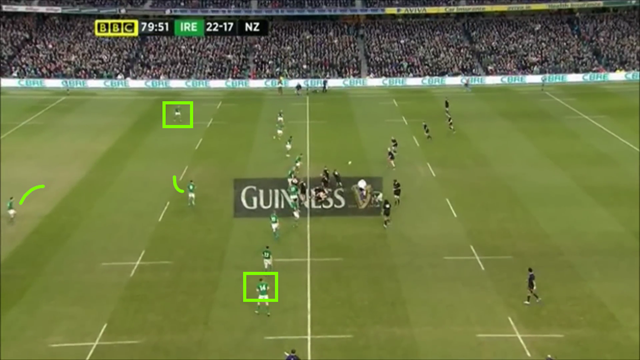

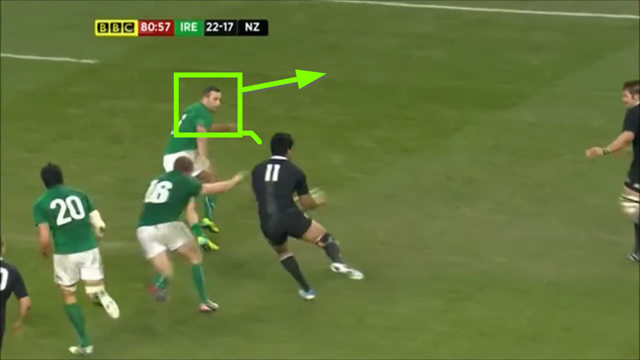

The two snapshots, taken 32 seconds apart, illustrate the Irish defensive attitude when the All Blacks attempted to shift the ball into the 15m corridor on their left-hand side. The back three are looking to move through the gears of their semi-circular rotation, with the #9 operating as a sweeper in behind the line.

In both instances, Ireland enjoys a one-man advantage out to their left (6-5 in the first example and 7-6 in the second) but they are aligned passively, with the wing playing ‘off’. They are not using the extra man to attack the ball.

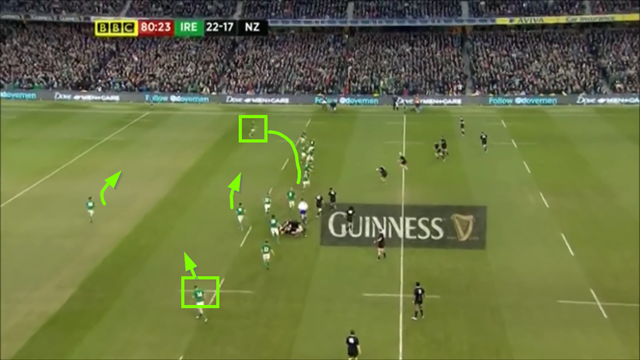

Now let’s look more closely at the attitude of both the Ireland wings as the ball is moved into their zone:

There is zero pressure on the second pass from Aaron Cruden to Ben Smith, and the Irish wing (#14 Tommy Bowe) has eyes only for the attackers outside him, leaving the drift to pick up Kieran Read underneath.

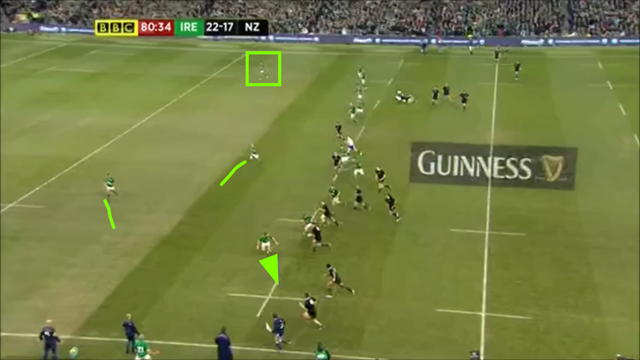

The same situation was replicated on the other side of the field moments later:

Once again, the second pass between Cruden and Julian Savea is made in comfort, and the defending left wing (Dave Kearney) is set ‘off’, he is playing the man rather than the ball. This gives New Zealand the width of the paddock on offence, and they exploited it to earn the ultimate reward only 20 seconds later:

There is no pressure on the second delivery, even in a position less than 10 metres from the Ireland goal-line, and the Kiwi ball-skills are far too good to let the opportunity slip once it has been created.

Summary

You can scarcely imagine the same passage of play being repeated against a modern rush defence. A defensive side like France (coached by Shaun Edwards) or South Africa (Jacques Nienaber and Felix Jones) would be forcing the issue on the edge far earlier and denying access to the full width of the field. Part Two will examine just how the Springboks achieved that aim, and returned the knotty problem – can New Zealand teams navigate a top-quality rush defence? – into the Kiwis’ court, at the 2023 World Cup final.