The opening round of the 2023 Rugby World Cup which represented a big victory for defence over attack. In all the top four games – France v. New Zealand, South Africa v. Scotland, England v. Argentina and Wales v. Fiji – the sides which tackled the most and built the fewest rucks triumphed.

In three of those four matches (excluding South Africa v. Scotland) the winning teams set 36 fewer rucks and made 96 more tackles on average. In England’s case, they did it with only 14 men on the field for 77 minutes, with the Pumas chalking up their only try of the game in the final minute of proceedings. With such alarming stats, one could be forgiven for wondering where success for the more attack-minded teams is going to come from.

The one glimmer of light was the performance of Ireland against tier-two Romania. As Ireland have shown consistently in their rise to the #1 spot in the men’s world rankings, you do not have to win the lion’s share of collisions in order to play winning attacking rugby. It is still possible to find space in multi-phase attack if you have the will, the structures and the personnel to do it.

Listen to these words from the mouth of attacking philosopher-guru (and The Rugby Site contributor) Brian Ashton, written more than 10 years ago:

“I watched the Lancashire Cup final, in which the two sides sought, in wholly contrasting manners, to lay hands on a much-desired trophy.

“Team A tried to dominate proceedings in the traditional fashion, using their forwards to hammer away at the opposition defence in what was obviously a pre-discussed manner, thereby creating ever-slower possession for themselves and eventually coming to a standstill. The players in the wider channels were mere appendages, used only as an afterthought, if at all…

“In the opposite corner, so to speak, were Team B… They maintained a challenging attacking shape, targeting the 13-plus channels as potential avenues of reward. This immediately opened up the field and created scoring possibilities that generated a collective sense of uncertainty in the defending team’s mindset.

“By following a corridor of complete predictability and certainty, Team A were repelled time and again by heavy-duty tacklers who were only too happy to occupy a space between five and 10 metres wide. Team B had the vision, the expertise and the courage to explore the more poorly-defended parts of the pitch, constantly creating a corridor some 25 metres wide in which to test their opponents’ technique and resolve.”

https://www.independent.co.uk/sport/rugby/rugby-union/news-comment/brian-ashton-teams-could-run-up-a-cricket-score-if-they-attack-the-corridor-of-uncertainty-7737896.html

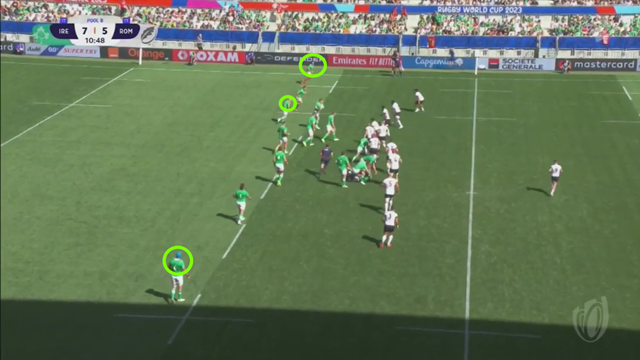

With Ashton’s words still ringing in our ears, let’s look at a sequence which occurred between the 11th and 12th minutes of the Ireland-Romania game. The attack started from a lineout on Ireland’s own 40m line:

<p.

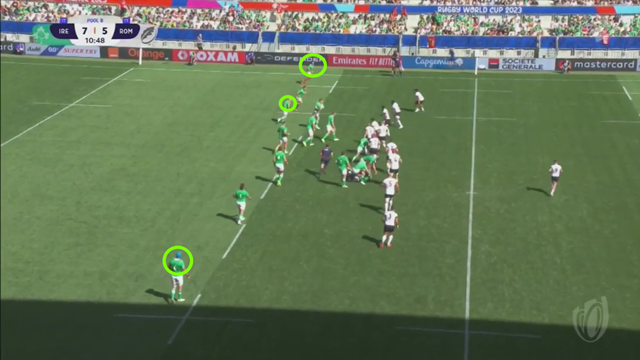

The first key to Ireland’s success is their ability to find, but not consume, width on a rugby field. It takes them two phases to reach the left edge of the field. The blind-side wing (typically Mack Hansen but in this instance Keith Earls) joins the open-side attack, while lock/back-row ‘ranger’ Tadhg Beirne (in the blue hat) mans the near-side touch.

When they play the ball back in off the left side-line, Ireland already has a small advantage in width over the Romanian defence:

After only four phases of attack, the widest player on the right side of the field (Beirne) is Irish – and he is the only one still occupying the space from the 15-metre line outwards.

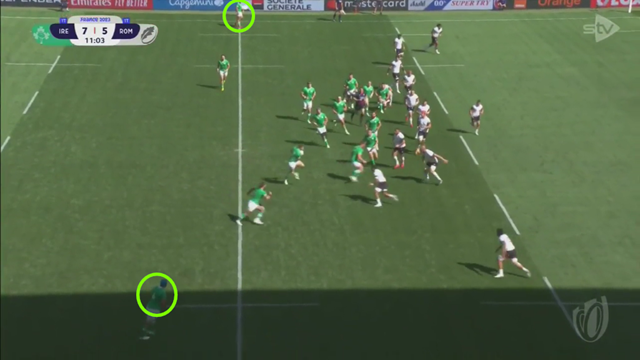

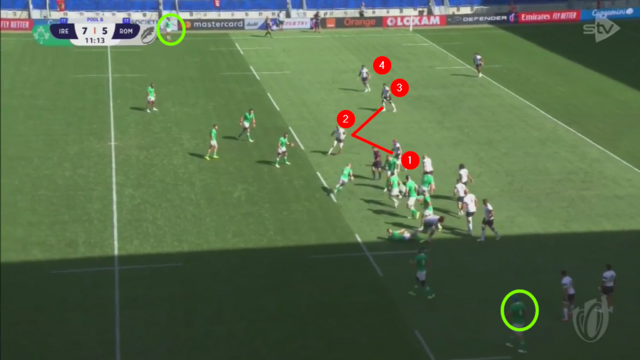

What is the effect on the defence? It stretches spacings between tacklers, who always need to be mindful of an attacker beyond them. The creation of width makes for uncertainty, loosening up room for attackers to test their opponents’ resolve underneath it:

Reversing the conventional formula (‘go through them in order to go around them’) requires precise passing, and the collective will to attack the space directly ahead of the ball-carrier in the action of receiving the ball. Ireland has both, and in the screenshot with their two widest attackers overlapping the Romanian defence on either edge, the structure in the middle is already beginning to collapse:

In this case it is powerhouse centre Bundee Aki who makes the big ground-gainer in contact, one-on-one.

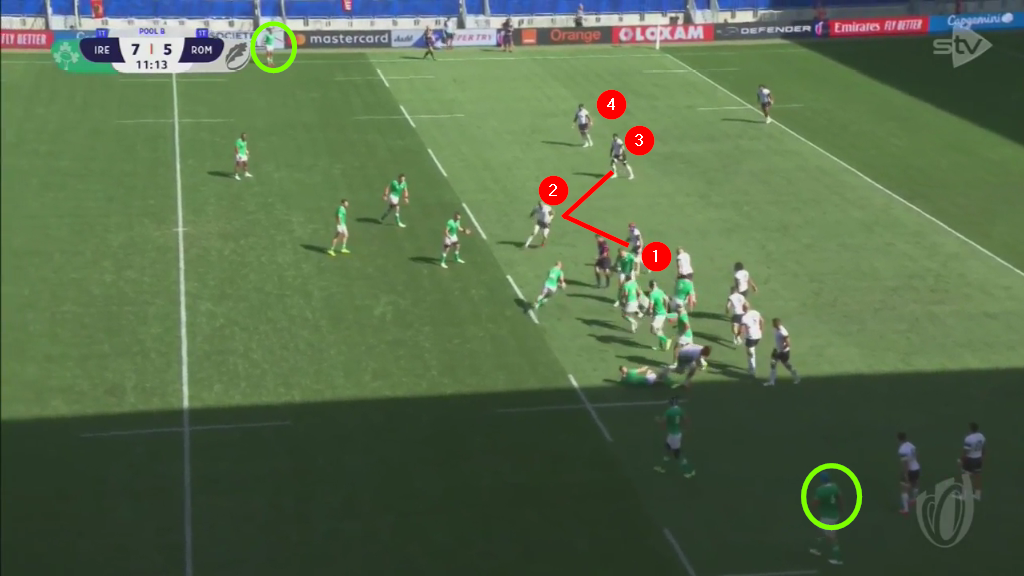

It was a case of ‘rinse-and-repeat’ as the sequence reached its climax on the 7th and 8th phases:

Ireland shifts the ball to Beirne on a string of passes a stride or two from contact, and that is the ‘tin-opener’ for the next play, where Peter O’Mahony has already spotted the disconnects in the Romanian midfield defence:

Summary

Two defenders are retreating towards their own goal-line as the ball is played, and they are in no fit state to present a co-ordinated resistance on the line to the better-organised Irish attack. Attack space ahead in the receiving stride, and accurate inter-passing will do the rest.

Ashton again: ‘Retain [attacking space], don’t consume it… The ideal is to have the receiver hitting the ball in the act of attacking the defensive line. Guess what this encourages? Correct: the short passing game, the key that unlocks every door.” Amen to that.

.jpg)

.jpg)