Rugby coaches love their abbreviations. They are convenient, and add an air of mystique to some of the processes in the game. Two of the most popular abbreviations right now are “KBA” (‘Keep Ball Alive’ – a brain-child of La Rochelle coach Ronan O’Gara) and “LQB” (Lightning-Quick Ball – the ability to recycle ruck ball in less than three seconds).

Both were present in recent comments by Harlequins attack coach, ex-All Blacks number 10 Nick Evans:

“There has been a bit more freedom and that is related to the way we [Quins] train now with a lot of gaining space drills and a lot around off-loading to create LQB.

“With the players we have got, I don’t want to put them in a box and say ‘in this position, you do this’. We have a detailed framework how we want to manipulate teams, but we want guys to make decisions on the pitch and create scenarios and to find different solutions.

“I know that [Ronan] O’Gara has talked about KBA and we have a similar thing with Lightning Quick Ball and our kicking strategy is designed to create something which could force a turnover contest, or kick for set-piece so that we can attack their set-piece. All our language around kicking is about attack and our players understand it is part of the game and when we don’t get LQB we have the ability to kick and create.” https://www.rugbypass.com/news/rising-coaching-star-nick-evans-is-a-fan-of-lqb-rather-than-kba/

Coaches rarely refer to the speed of ball-production, or keeping the pill alive at the maul. That is seen as more of a physical grind or arm-wrestle which tends to finish with either a penalty or a try, especially in positions close to the opposition goal-line.

In fact, there are methods of generating ‘lightning-quick ball’ on the lineout drive too. It is quite possible to avoid the grind, especially when the defensive side picks the sack or the counter-jump as their weapon of choice.

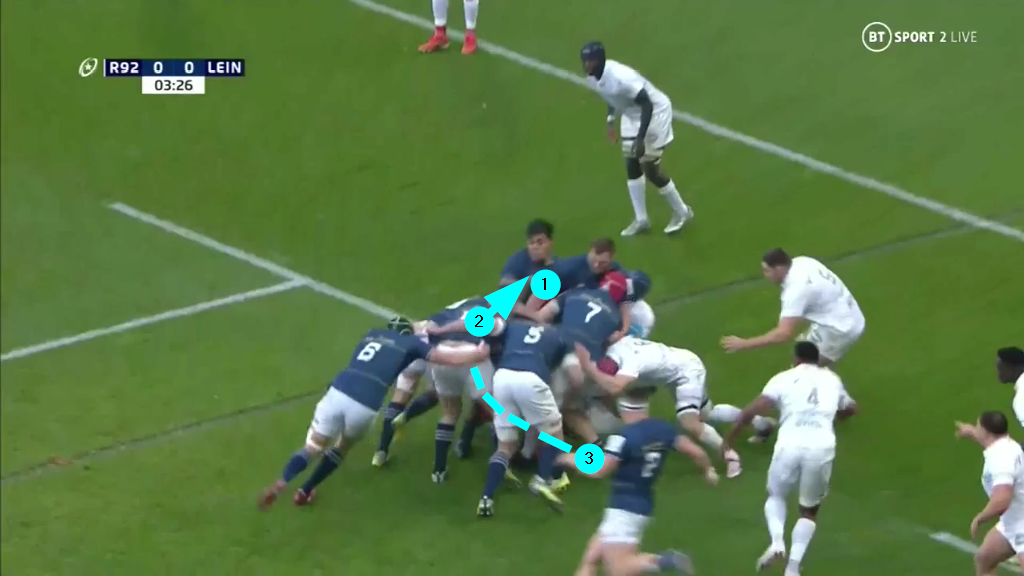

The following examples come from the recent Heineken Champions Cup game between Racing 92 and Leinster. The Irish province generally eschewed the long arm-wrestle for ground in favour of quick-hitting drives from the lineout:

The throw goes to the back of the line, where the Racing number 8 (in the sky-blue hat) tries to sack the receiver immediately after the catch is made. In this scenario Leinster do not attempt to wait for the thrower (hooker Dan Sheehan) to wheel into position to become the ball-carrier at the back of an orthodox ‘slow drive’. Instead, the latcher (number one Andrew Porter) takes the ball through immediately before formations on both sides consolidate. The outcome is a penalty to Leinster and a yellow card (for repeated offences) on Racing.

At the start of the game the Irish province had scored a try from exactly the same platform:

After the catch is made by second row Jason Jenkins, the ball is transferred post-haste to Porter to avoid the sack with an excellent piece of KBA. The ball stays with him in the second layer of the drive all the way to the in-goal area, with Sheehan little more than an interested bystander.

Both of the players who Racing might have been targeting as the ball-carrier – Josh van der Flier at halfback “+1” (in the red hat), and thrower Sheehan running in from the side-line – are either occupied in another role or are not a factor in the play. Van der Flier moves in as front lift for Jenkins and Sheehan never makes contact with the ball at all.

The recurrent themes are ‘lightning-quick ball’ and ‘keep ball alive’ – but with the pill in hand at the maul rather than on the deck in the ruck:

Van der Flier latches, the maul drives forward and Sheehan only takes it on at the very end of the play. One final example:

In this case the throw goes to the front/middle and the sack by Racing is more successful, although the transfer to Van der Flier in the second layer of the drive has already been made. Once again, there is no thought of waiting to add Sheehan to the drive in the third layer. As soon as the Ireland number 7 sees space ahead of him (as the latcher), he moves into and through it to keep the tempo of the attack high. The ball is very much alive and the speed of the next ruck will be lightning-quick.

Summary

The principles of LQB and KBA don’t have to be confined to the skills of offloading and quick ruck ball production in open play. They can even be applied to what is traditionally the slowest-developing form of attack, the lineout drive. Quick transfers between catcher and latcher, with the ball staying in the second layer of the drive rather than awaiting the hooker’s arrival in the third, pay rapid-fire dividends, particularly against the sack and the counter-jump. Tempo can be established right from the set-piece, and a prolonger arm-wrestle is by no means obligatory.

.jpg)

.jpg)