In this article over four years ago,

https://www.therugbysite.com/blog/attack/the-importance-of-reloading-and-understanding-space

I used a Rugby Site training session run by Scotland head coach Gregor Townsend as a platform for exploring the importance of reloading, and getting back into relevant positions quickly on attack.Townsend himself commented during the session:

“My coaching philosophy is based on what I learned as a player and what drove me as a player – and that’s finding space on a rugby field."

“I believe there’s always space on a rugby field, no matter how organized defences are. The purpose of all attacking play is to discover where defences are weak.”

He has taken that philosophy all the way into the national side, and the first round of the 2023 Six Nations showed how far his charges have come in one particular area of attack, the kick return.

A good kicking game is still the safest way to make progress at the highest level, and the new England head coach Steve Borthwick is very much a disciple of it. When he was still coaching at club level, his Leicester Tigers contributed liberally to an English Premiership final against Saracens in June 2022 featuring no less than 105 kicks in total. Leicester had the highest average number of kicks per game in the league that season, and were the only side to kick regularly for over 1000 metres per game.

Nothing changed much in the first round of the Six Nations against Scotland at Twickenham. There were 70 kicks in open play and 79 in total, an average of one kick every minute. The problem to be solved for Townsend’s Scotland against Borthwick’s England could be described as ‘how to identify the right moment to return the ball in hand, rather than kick it back again’.

Many of the kicks launched by the England halves were long-and-upfield, and far beyond the range of a typical 30m contestable box kick. The contest became a race to regroup, and on three significant occasions the men in blue accomplished that task more efficiently in counter-attack than those in white did it on defence.

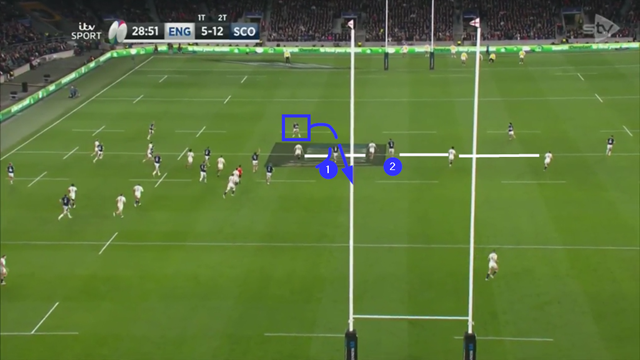

The first example occurred in the 29th minute of the first half.

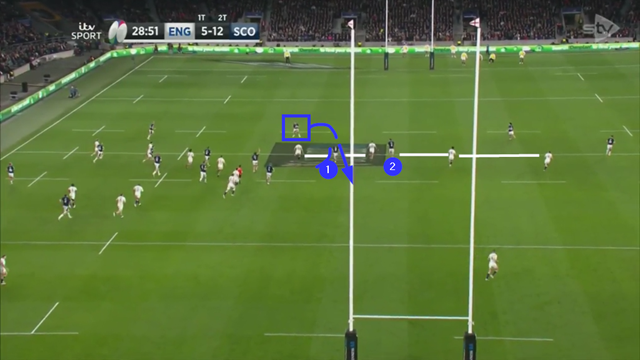

The ball is kicked long, over 40 metres by England scrum-half Jack van Poortvliet, well beyond contestable length and over the halfway line. How did Scotland win the ‘race to regroup’? The key moment arises when the returner (big Scotland left wing Duhan van der Merwe) makes first contact with the line of chasers:

Van der Merwe has an obvious job to do returning the ball, and he does it outstandingly well. But his two principal ‘enablers’ are “1” (Scotland hooker George Turner) and “2” (number 6 and captain Jamie Ritchie). Their task is to run back in between the line of English chasers and create a break in defensive integrity.

Turner tracks back between the first two defenders (Owen Farrell and Joe Marchant) and Ritchie drops into the outside channel, in between Marchant and Marcus Smith. When Van der Merwe picks channel “1” on the return, Turner is standing quite naturally in between the Scotland wing and the man most likely to tackle him, Farrell. He is entitled to support the ball, so long as he doesn’t attempt to cut across Farrell’s line to the ball-carrier intentionally, in an act of deliberate obstruction.

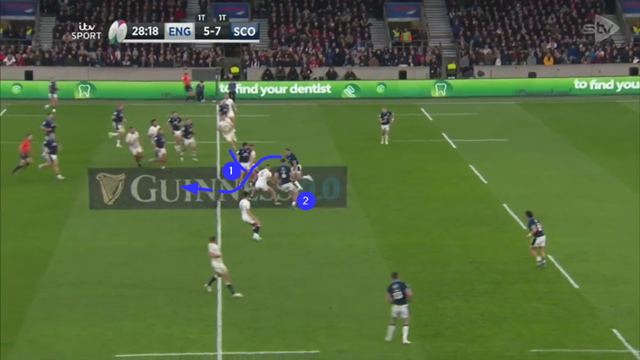

The second instance occurred at the end of the third quarter, and again leaned heavily on the work rate of the Saltires’ skipper:

This is a freeze-frame of the key moment. England have kicked long into the Scotland 22, and the men in blue have spun the ball to van der Merwe out on the left to set the first ruck. The success of the return thereafter is founded on the race to regroup. How quickly can “1” Jamie Ritchie (in the headband) drop back into a linking position, wide right? Can the circled pod of Scottish forwards, plus scrum-half Ben White, reload fast enough to allow “2” Finn Russell to join up the midfield and edge attackers on the pass? Here is the answer in real time:

If White doesn’t service the first ruck, and if the pod of three forwards do not retire to form a front wall for the ball behind to Russell; if Ritchie doesn’t make the 35m sprint to recover from a position beyond the halfway line to within his own 22 and provide the connection out to the right wing; if any one of the links in the chain fails, no return would be possible. But all perform their tasks off the ball, and the break is made. By way of contrast, England are a step slower reorganising on defence.

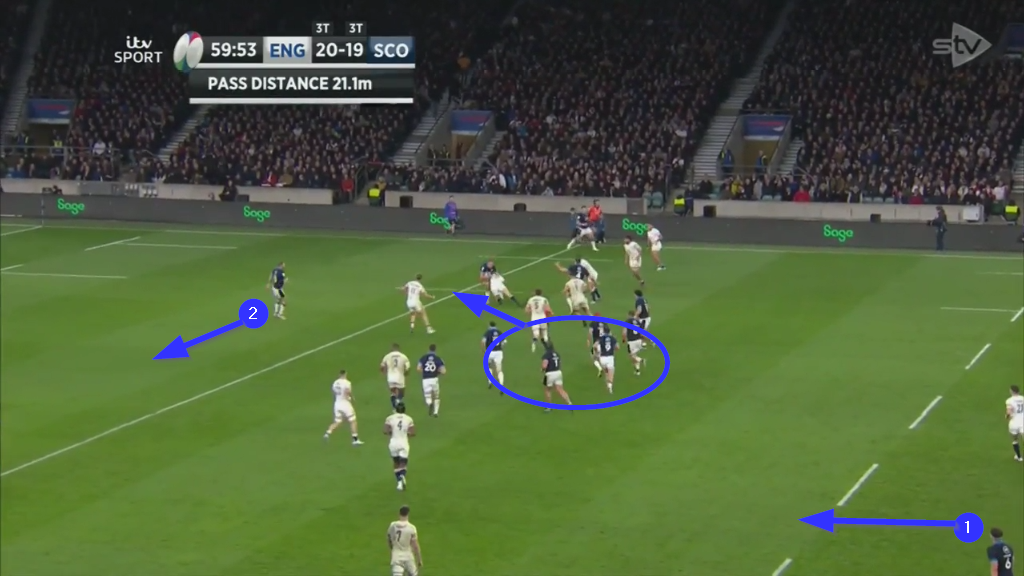

The decisive try of the game also came by way of a long-field kick return. The activity of Scotland’s replacement scrum-half, number 21 George Horne, was a joy to behold:

Horne starts by shielding the kick receipt by Russell on the wide right, then he runs a typical #9 ‘cheat line’ to service the first ruck over on the far left. He services the next ruck in midfield too, before becoming the crucial first man to the breakdown after a long break down the right:

When Van der Merwe finishes once again on the left on the following play, it is in the knowledge that George Horne oiled the wheels of the kick return machine on the previous three phases:

Who is the first man up when Van der Merwe crashes over the goal-line? That’s right, it is George Horne. He has covered approximately 200 metres in the 45 seconds that the sequence lasts while shielding the kick receiver, servicing two rucks and cleaning out after a break.

<b<

Summary

It takes a lot of hard work to create a platform to unlock a good opposing kicking game, and the chase which backs it up, on counter-attack. Players willing to run intelligent lines of interference in support, or making recovery sprints to regain position and make themselves relevant, are truly worth their weight in gold. That is the very best way to find space on a rugby field. Just ask Gregor Townsend.

.jpg)

.jpg)