Top sport is all about pressure, and how you handle it. Pressure to win, pressure to succeed, pressure to score. It can easily become overwhelming. The pressure only increases in situations where expectation becomes a factor. You’re expected to beat a certain opponent easily, or to finish off a game that is all-done-bar-the-shouting, or score a try close to the goal-line, and it doesn’t happen. There can be a negative mental prompt which sets off a catastrophic chain reaction internally.

If you play it safe, it can often lead to the sporting syndrome of ‘tightening up’ psychologically. Typically, sportsmen turn to increased focus on the detail of their performance, a technical hypervigilance – and that only makes things worse.

They fixate, losing contact with the what their opponent is doing and the environment around them, the flow of events. All sense of context falls away. At worst, it results in the phenomenon known as ‘choking’ – a complete psychological block, and an inability to allow the athletic body to do what it does best.

Elite sportspeople have developed the knack of maintaining concentration while enjoying the circumstances around them. This is the point-of-balance that the ten-time Golf Major winner Annika Sörenstam has described quite eloquently:

“People are watching, this putt means this. Or: This is a tough hole. Or: It’s an easy hole and I really should make it. All these things around you have an effect on how you feel, and how you perform.

“You have to have a positive mind, you have to stand there and be tension-free. If you stand there and are worried about everything, it’s hard to swing.

“When I play my best, it’s free-flowing and relaxed, no tension – just focus and have a target, but you’re relaxed and [let] your muscles perform. There’s nothing worse than when you try to do something and it’s all tension and pressure and you can’t breathe properly.”

“Of course, I felt pressure. But it was a fun pressure – I wanted to see if I could handle it, just staying true to myself and believing in myself coming down the stretch.” https://www.theguardian.com/sport/2020/nov/05/under-pressure-why-athletes-choke#:~:text=Failure%20to%20manage%20anxiety%20and,reaction%20to%20pressure%20or%20stress.

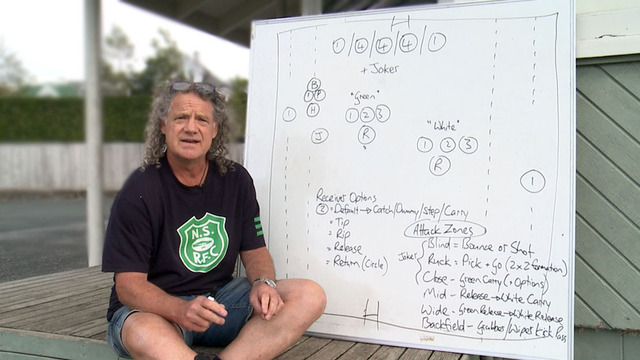

In rugby terms, that step up in pressure is often felt by teams attacking close to the goal-line. The expectation is that they will probably score a try from that start-point only a few feet away from success, and it can lead to a version of the ‘tightening up’ described earlier.

The focus can so easily narrow to the space right in front of ball-carrier, that the opportunities available with the benefit of just one extra pass can be neglected in favour of fruitless physical bashing at a barn door. How to relax, and feel where the space is?

From penalties awarded on the opponent’s five metre line, the main options are twofold – either kick for touch and drive the lineout, or take a tapped penalty and try to barge your way over from positions further infield. The magic dust of the extra pass can make life a lot easier for the attacking side:

This instance comes from the semi-final of last year’s URC competition played out between Leinster from Ireland and the Bulls from South Africa. The tap-and-drive by the Bulls number 8 forward (in white) attracts three Leinster defenders (in blue) to the expected point-of-contact, only for a reverse ball to be slipped from Elrigh Louw to hooker John Grobelaar (in the red hat) for an easy score.

Leicester Tigers scored a two-part version of same try on their way to victory over Saracens in the 2021-22 Gallagher Premiership final:

Yes, there is brute force from prop Ellis Genge on first phase, but then the extra pass down the short-side is made to create space for South African number 8 Jasper Wiese to score on second.

Saracens may have taken their cue from this piece of ingenuity when they played their perennial rivals the Exeter Chiefs on New Year’s Day:

It looks like England prop Mako Vunipola will dive head down, straight for the line after tapping the ball to himself. In fact, he is looking to make the extra pass to his brother after drawing three Exeter forwards to the initial point-of-contact. Billy doubles down by slipping a neat offload to his back row mate Andy Christie, who has only to run past an arm tackle by the Chiefs’ number 10 Joe Simmonds to convert a simple try.

Likewise, it is quite possible to make the extra pass in the course of a lineout drive itself. Compare these two instances, the first from the same game, the second from the 2021 end-of-year tour encounter between Scotland and Australia:

Summary

Defensive teams automatically concentrate their lineout maul defence around the receiver, so why not have him/her make the extra pass off the top and move the blocking front to another area? That zone is behind England’s Maro Itoje in the first instance, and in front of Scotland’s Jamie Ritchie in the second. In both cases, the subsequent drive is opposed by significantly weaker resistance than if it had remained at the first point-of-contact.

The willingness to make this kind of play illustrates the kind of balance Sörenstam described in her comments about the importance of staying ‘free-flowing and relaxed, no tension’ under pressure. There is the obvious physical point (to score a try) but there is also a psychological accent too. Even when the attacking team can see the whitewash under their noses, they don’t tighten up but see the space in the big picture. They have an outcome in mind, but they have fun, making an extra pass in order to achieve it!

.jpg)

.jpg)