Forget the 1-3-3-1 and the 2-4-2. In the modern professional era, more often than not there is simply not the time available to fit snugly into those attacking shapes, especially from more unstructured start-points like kick or turnover returns.

The new directives for quicker resolutions at the ruck, introduced back in 2020, have made a definite impact. During the 2022 Six Nations, Ireland were building more than 100 rucks per game with a 97% retention rate, at an average ruck speed of 2.9 seconds per breakdown. In the 2022 Rugby Championship, the All Blacks were building 88 rucks per game at a 94% retention rate with the same average speed of ball production.

The outcome of this glut of LQB is that both defence and attack now have less time to organize and get into shape for the next phase. For the offence, that means attacking structures have to be more compact, and there has to be more interchange of roles in the forwards. Time is short.

The days when you could happily position two back-rowers and a hooker in each wide channel, and let them link with the backs play-in, play-out – as the All Blacks used to do with the likes of Kieran Read, Jerome Kaino and Dane Coles – are long gone.

Likewise, the 1-3-3-1 formation often transforms into a 1-3-2-2-1 or a 3-3-2 as players shift from one channel into another. The situation of more fluid, and more is being asked of the ‘spares’ who used to play as the “1’s” or “2’s” in these scenarios.

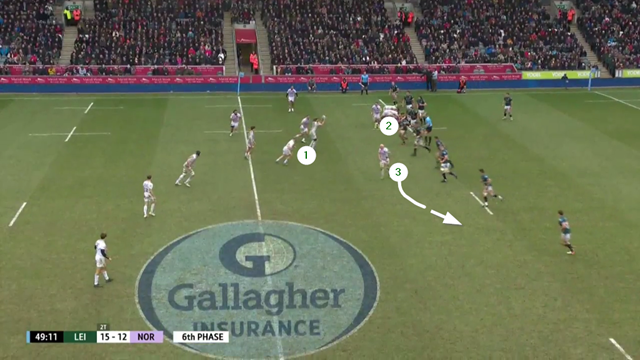

One of the top attacking sides in the English Gallagher Premiership, the Northampton Saints, showed what is now required in their recent match against the current champion team, the Leicester Tigers, at their home ground Welford Road.

The Saints attacked with two three-man forward pods, composed principally of the two props and second rows, plus number 6 Angus Scott-Young. The role of sixth man in pod play was filled by one of the ‘spares’ – either replacement hooker Robbie Smith (#16), number 8 Juarno Augustus or number 7 Aaron Hinkley. The range of their movements as Northampton played their way back into shape off kick returns were instructive.

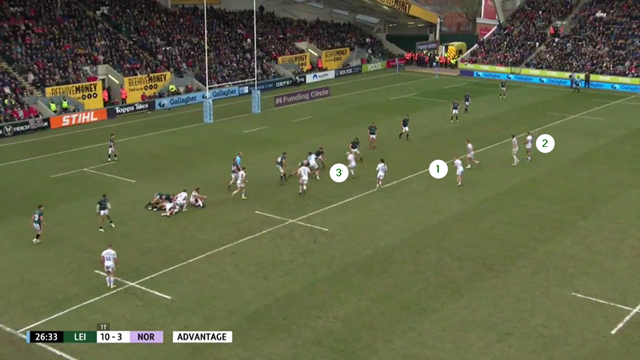

The longest return sequence occurred in the 26th minute of the first period:

This is second phase. Both “2” Augustus (who tended to drop back as an extra returner on the left) and “1” Smith are absorbed at the first ruck on the left, with “3” Hinkley carrying as the spare added to the first of the two pods. By the following phase, Hinkley has already worked his way out to the right to service another ruck after a shift wide by the Northampton backs.

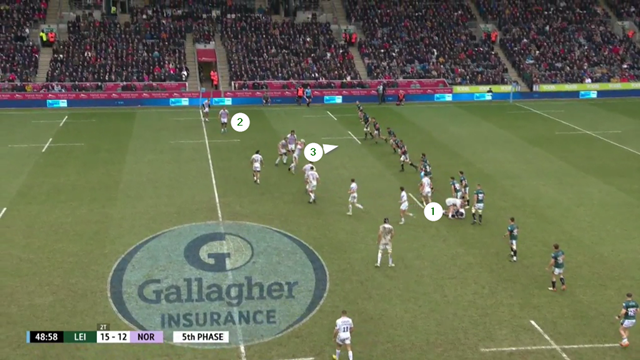

Within the space of another five phases, he had been joined by both Augustus and Smith:

Hinkley and Augustus are servicing the first ruck in the clip, and Smith the second (the ninth overall) as play moves across to the right side of the field. They do not stay in their channels, and Augustus carried on the following play with Hinkley as his main cleanout support. The two three-man pods swing back and forth in the area between the two 15m lines, and the spares follow the ball. The provision of width is left to the backs alone.

By 12th phase, all three men have worked their way to the middle-left of the field and secured a double penalty advantage. Width left is supplied by Northampton’s #11, 12 and 13, Hinkley has added himself to the carrying pod and Smith and Augustus are facing the Leicester posts in midfield.

The extra work done off the ball by ‘the spares’ had the effect of wearing down the Tigers kick return defence as the game developed:

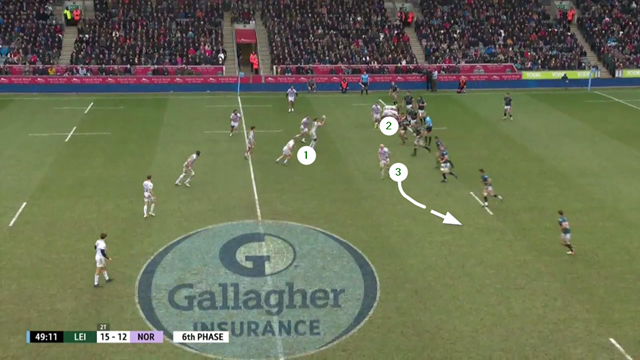

By 5th phase from another kick return, all the Saints’ forwards are in the left half of the field and all the spares are within 10 metres of the ball. By the strictest definition they are ‘out of channel’ – all except for Augustus – and it is left to the Northampton backline to provide decisive width on the next play:

Augustus has serviced the previous ruck, Smith has added himself to the second forward pod, and Hinkley is already frantically signalling for, and tracking towards the space wide right, which full-back James Ramm promptly sees and exploits with a deft offload. Like any good 7, he is still on hand when the try is scored.

The spares proved their utility value throughout the second half, especially from kick return starters:

Augustus carries from the backfield with Hinkley’s replacement Sam Graham cleaning out over the top of him. Smith has added himself to the second forward pod, which like the first is operating well within the left 15m zone. It is left to the two props to prise open a hole from their midfield “2” and create more space for the backs out wide on the following phase.

Summary

The speed of modern ruck ball has now increased to a point where formations have had to become more flexible to maintain momentum and fan the flames on attack. Rigid 2-4-2 and 1-3-3-1 structures transmogrify to 1-3-2-2, 1-3-2-1-1 or 3-3-2 depending on the situation, and they are more compact and occupy less space on the field than they did before. The spares go where their services are most needed, rather than moving up and down vertically in their allotted channels. It is a new world on offence and work rate off the ball is everything.

.jpg)

.jpg)