How to fake the kick and make the metres on exits

One of the besetting problems in professional rugby is how best to get out of your own half, what is now known as ‘exit strategy’. With ball-retention rates now regularly topping 95%, if you cannot get out of your own end emphatically enough, you will very soon find yourself back in your own half, still on defence.

Typically, exit strategy involves the use of the kick, because the boot is the easiest way to move the ball upfield and relieve the pressure. However, a good defensive team will load their backfield in order to make the expected kick a much less attractive option.

If they expect you to kick long, they may drop three or four players into their backfield to return the kick with interest. If you kick high and short, they can rotate towards the side-line and block the chasing lanes.

Increasingly, exiting teams are looking for more subtle ways of finding space, to make their exits really count. The opening weekend of the Six Nations tournament in the Northern Hemisphere, and Super Rugby in the South, both provided some excellent examples of what those methods might be.

One of the most common methods of exiting from your own territory is via the so-called ‘box kick’ off the number 9. This form of exit is generally low-risk, because the ball is kicked high and parallel to the side-line, and lands where the chase is likely to be at its hardest, and at its most dense.

The problem with the box-kick is that the ball does not tend to go very far, between 20 and 30 metres. If the opposition can secure the ball, they will generally find themselves in good field position, somewhere in between your 22m line and halfway.

There were a number of examples over the weekend of exiting teams ‘showing’ one exit and then delivering another – constructing what looked for the all the world like a box-kicking scenario off their number 9, only to shift the play sharply towards the other side of the field.

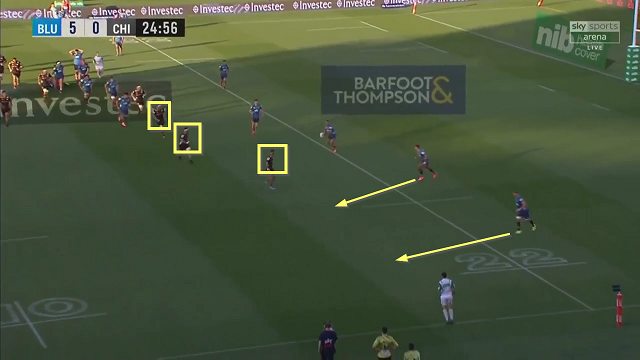

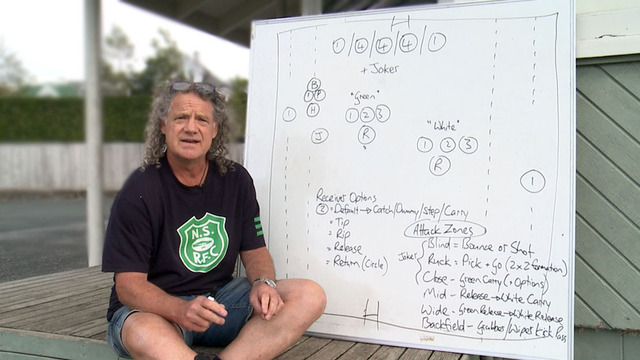

Let’s take a look at some of the detail, and how the mechanics of the ‘fake exit off 9’ work. The first example comes from the Super Rugby match between the Blues and the Chiefs:

The Blues number 9 ‘shows the fake’ by calling in two forwards to the ruck in order to form a protective shell on his right side, a ‘caterpillar’ from which he will be able to launch the kick without interference from the defence.

At 24:53, he suddenly switches his foot positioning and passes out to the opposite side. At the key moment, the Blues have exactly the exit scenario they want:

The last Chiefs defender is still well inside the far 15 metre line, and he only has two forwards underneath him for company. Therefore, there is no pressure on the ball, and the Blues have two extra players in the wide channel out towards the left side-line. One accurate pass is all it takes to get the ball outside, and final kick finds touch only ten metres from the Chiefs’ goal-line.

Instead of the expected 20-30 metre gain off an orthodox box-kick, the Blues have gained 60 metres and it is now they who are applying the pressure.

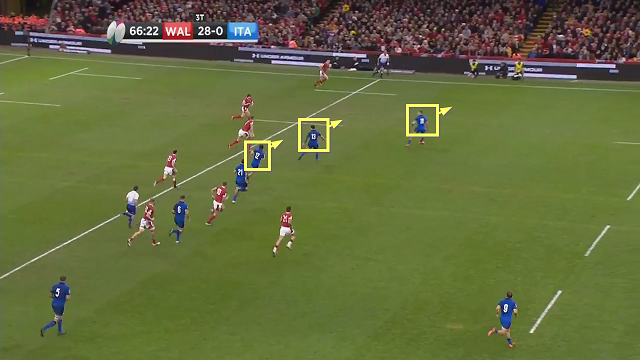

The theme was repeated in the opening game of the Six Nations on Saturday afternoon, played between Wales and Italy.

Here the start point is a lineout drive rather than a ruck. The ball has been held in the maul for at least 10 seconds before replacement scrum-half Rhys Webb decides to play it. Once again, the halfback’s feet have been pointing towards the near touch-line, shaping for the box-kick along it.

When Webb changes direction and passes out towards his left, there is a big change not only of direction, but also of tempo in play. The screenshot shows that the Italian defence is struggling to come to terms with that sudden shift:

Wales only have to make simple passes along the line, with the Azzurri defenders committed to drifting across field. There will be no defensive rush, and no pressure on the ball.

The Welsh left wing Josh Adams is able to take play well across halfway, and Wales are still on the front foot and in possession of the ball at the end of the phase.

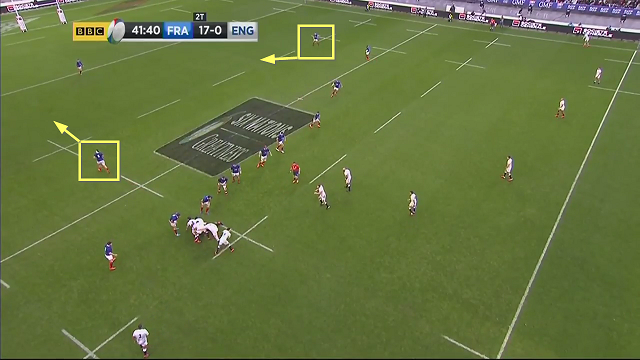

The final example, from Sundays’ game between France and England in Paris, is perhaps the most revealing of all, because of the ‘bird’s eye’ view granted by the overhead camera:

The position is much further upfield (on the French side of halfway), but the England scrum-half Ben Youngs is again shaping for a high kick from the base of a long ‘caterpillar’ ruck.

With the benefit of the overhead camera, it is easier to see what impact Youngs’ set-up has on the movements of the French backfield:

The French number 8 is dropping back to receive the expected high kick, while the final France defender on the far side is already rotating towards the middle of the field.

For a moment, space has been created for long diagonal kick by England number 10 George Ford, and he exploits the opportunity by finding touch only a few metres from the France goal-line.

A little subtlety and attention to detail goes a very long way! Instead of kicking the ball automatically, the Blues, Wales and England all found ways to create space for their kicking or passing games on the ‘wrong’ side of the field, and the success of the initial deception meant they were under little or no pressure while the process was underway.

.jpg)

.jpg)