How to blind-side your opponent from scrums!

Defence in the modern game is built around the speed at which the defensive line can move up and mount pressure on its opponents. Both Sir Graham Henry’s and Rodney So’oialo’s modules on The Rugby Site illustrate the importance of igniting, and then sustaining momentum on defence. The idea is to take the initiative away from the attack.

So the question for the offence becomes “How can we offset that momentum? How can we take away some of that speed?”

One of the most effective fundamental solutions is the use of the blind, or short-side – or the creation of attacking platforms in the middle of the field. The reason that this recipe works is that a defence is very rarely able to mount effective line-speed on both sides of either a set-piece or a breakdown, so it tends to focus on generating pressure on one side only.

Typically, they will choose the wider side of the field to mount the rush. The more passes that are made across the width of the field, the more opportunity there is to rush up on one of the outside receivers and take man and ball together, or break in between the passer and his target to make an interception.

The blind-side is often protected by slower or less dynamic defenders and the attitude is more passive. If the planning and execution is accurate, this gives the attack the opportunity to create chances without worrying about the potential disruption created by line-speed.

Likewise, if there is a set-piece or ruck in a central position, the initiative is generally in the hands of the offence, because the D cannot be certain where the main attacking effort will fall. This fact dilutes defensive line-speed quite naturally.

One of the best situations in which to exploit a scarcity of line-speed is from scrum, where there are fewer players manning the ramparts, and each with larger line-splits to defend. The All Blacks are masters at flooding a one side of the field, and ‘misdirecting’ the D to exploit the blind-side in these scenarios.

Let’s take a look at a couple of examples. Ever since he became New Zealand’s number one choice at first five-eighth after the 2015 World Cup and the retirement of Dan Carter, the New Zealand coaches have tried to find ways of utilizing Beauden Barrett’s speed and power when opponents have to defend against him in space.

One of the very best high line-speed defences the All Blacks have had to face in recent times is the system coached by Andy Farrell, for both Ireland and the British & Irish Lions in 2017.

In the game against Ireland in November 2016, New Zealand successfully identified a situation in which the Irish defence would be unable to mount a rush, at a scrum in midfield:

The All Blacks have split their backs to both sides, with the majority of four (Barrett, centres Malakai Fekitoa and Anton Lienert-Brown and wing Julian Savea) all to the left, and the speedy Ben Smith and Israel Dagg over on the right.

The adjustment this formation causes to the defence is obvious in the shot from behind the posts as Barrett receives the ball on the left:

Three defenders have stay to mark Smith and Dagg and the possibility of an 8-9 move on the All Black right. This in turn means that Ireland will not be able to develop any line-speed on the other side, because the Kiwi first receiver (Barrett) will be the responsibility of Conor Murray, the Irish half-back.

The rest of the Ireland backs on that side have to adopt angles which enable Murray to close the distance on to Barrett, so that the structure becomes a passive holding operation, looking out towards the touch-line.

In the event, Murray cannot not get out to Barrett in time to make the tackle, with the target moving away from him at speed:

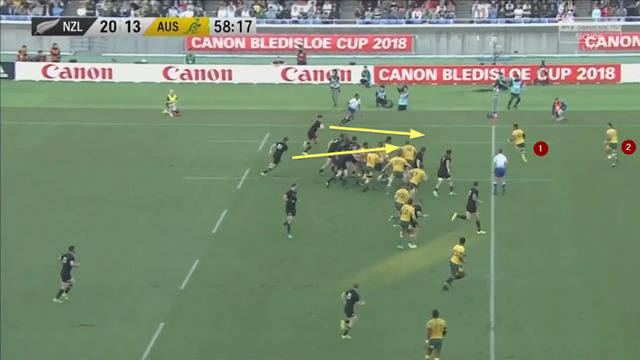

Australian coach Nathan Grey has meanwhile been busy building a high line-speed defence with the Wallabies. In the third Bledisloe match of the 2018 season at Yokohama, New Zealand showed how to neutralize that line-speed by misdirecting the defence, and returning ‘blind’ at a scrum on the left side of the field:

Again Barrett is the focal point of the play, but this time as a passer and support player rather than a runner. New Zealand know that the Wallabies will want to rush on the large open-side portion of the field, and they first encourage that line-speed to develop by making two passes (from Kieran Read to T.J. Perenara, and from Perenara to Barrett) out in that direction.

With the Australian back-row following the ball open-side as well, at the key moment the ball is switched back in the opposite direction. The two defenders on the blind-side (Wallaby number 9 Will Genia “1” and number 13 Israel Folau “2”) are passive, and like their counterparts in the Ireland game looking out towards the side-line:

The passivity allows New Zealand left wing Rieko Ioane to build enough momentum to drive through Genia and offload to Barrett in the challenge of Folau.

Summary

We live in the era of defences that want to build as much line-speed as possible – to deliver frontal tackles and create disruption and turnovers through hard physical contact.

The responsibility is now on the attack to create situations in which they can expect much more passive responses by their opponents. Scenarios in midfield (where the defence cannot mount a rush to both sides) or with a blind- or short-side provide those situations.

A lot of these prime attacking possibilities can occur from scrums, where there are fewer defenders trying to guard bigger spaces. Overloading one side with attackers, or using misdirection to trick the defence into driving up on the wrong side of the attack are great methods to overcome an aggressive rush. Grabbing and maintaining the initiative is everything, whatever part of the field you occupy!

.jpg)

.jpg)