There were a whole host of new law variations announced before the start of Super Rugby Pacific 2023. Most were designed to speed up play or increase the amount of ball-in-play time, where the Southern Hemisphere has recently fallen behind the North for probably the first time in rugby’s professional history.

The time allotted to the formation of lineouts and scrums has been reduced to 30 seconds and time allowed for a kick at goal to one minute. Water breaks were removed and a new review system for foul play has been instigated, in which TMO’s would investigate incidents and make their judgements while play continued.

From a coaching viewpoint, perhaps the most significant change was left to last:

10) Defending 9 not being allowed past the mid-line of the scrum [Modification Law 19]:

30. Once play in the scrum begins, the scrum-half of the team not in possession:

a) Remains on that team’s side of the middle line within 1m of the scrum, or

b) Permanently retires to a point on the offside line either at that team’s hindmost foot, or

c) Permanently retires at least five metres behind the hindmost foot.

Under the law still being applied in the current Six Nations, the ball is the offside line for a defending scrum-half: “Once play in the scrum begins, the scrum-half of the team in possession has at least one foot level with or behind the ball.”

In one hemisphere, the defending scrum-half can follow his opposite number around to the base and look to spoil the link from the base. Under the trial rules in the other, he has to retire, staying close to the scrum or dropping back to join the rest of the defensive line.

I first suggested this change over two years ago in an article for The Rugby Site!

Currently the offside laws allow the defensive half-back to ignore rule 19.31: “All players not participating at the scrum remain at least five metres behind the hindmost foot of their team.” Instead of awarding a penalty, why not require the number 9 to retire the full five metres, and all forwards to remain fully bound for the duration of the set-piece?

In the situation before the trial rules, the defending scrum-half has full licence to spoil at the base. This example comes from the recent Six Nations game between Italy and Wales in Rome:

Welsh replacement halfback Tomos Williams (#21) is free to follow his opposite number around to the base and create a sticking point when he goes to pass, and he is still an active part of the defence in cover when Italy are forced to kick the ball away down the right side-line.

At the extreme end, this permits the defensive number 9 to follow play all the way down the attacking line, and allows him to become particularly influential against plays designed for a wrap-around, or a second touch by one of the key receivers:

This example comes from a Rugby Championship match between South Africa and Argentina played a few years ago. The view from behind the posts illustrates very clearly how Springbok halfback Cobus Reinach is allowed to defend from the ‘wrong’ side of the ball.

Reinach chases his opposite number all the way down the Pumas side of the line, batting the ball down after the Argentine scrum-half looks to get a second touch off his #12 and finally picking the loose ball up on the left wing before scooting away for a turnover try. Several defensive teams have copied Reinach’s actions since, as this type of ‘wrong side’ defence has become especially effective against multiple touch offence.

Now take a look at a couple of recent scrums under the new rules, with the defensive halfback required to retire rather than follow the ball around to the base. Both instances come from the SRP match between the Brumbies and he Reds:

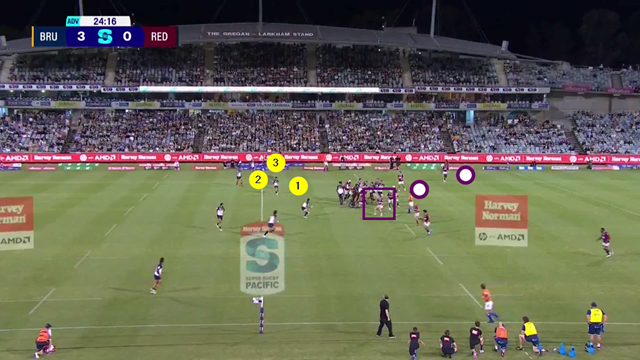

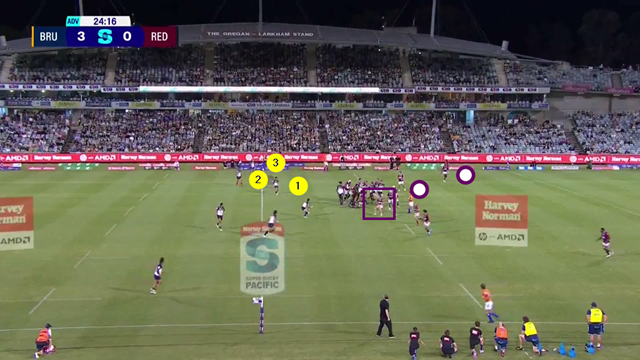

The Queensland scrum-half Tate McDermott retires well out of camera shot, allowing the Brumbies number 8 an unimpeded pick-up at the base and creating an advantage in numbers on the short side:

McDermott follows his opposite number (Nic White) around to the open-side but he is defending reactively as a nice 3-on-2 develops down the other side for the men from Canberra.

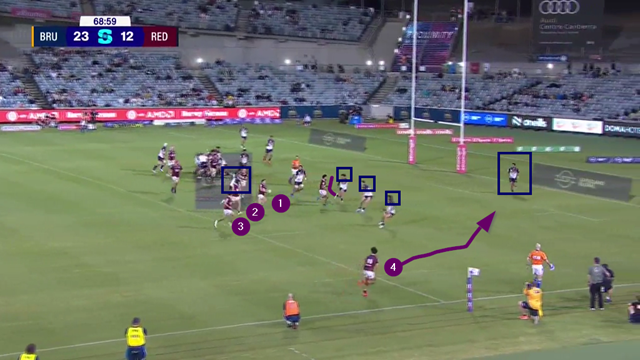

Late in the game, the Queenslanders showed just how effective a scrum attack can be when the defensive scrum-half can no longer chase down the line from the wrong side:

Firstly, there is no pressure on the pick-up by Harry Wilson at the base. Secondly, replacement scrum-half Ryan Lonergan is no longer a threat to his opposite number McDermott on defence; he is a step short of preventing the pass and subsequently, an inviting one-on-one in space down the right side-line, which Jordan Petaia converts into a score.

The earlier article concluded:

“Require the forwards to respect their original binds, and the scrum-half to respect a new offside line five metres behind the set-piece. Then, the attacking side will enjoy an advantage in numbers, and space to the promoted side of the scrum. Whatever course World Rugby chooses to take in the future, let us hope it will render ball usage from the scrum a necessity, not an option.”

Summary

It is good to see ideas to create clean attacking ball from scrums encouraged by the latest law-trials, and (potentially) the scrummage returning to its former status as a potent attacking weapon. It is one rule change which deserves exposure world-wide, not just in the Southern Hemisphere.

.jpg)

.jpg)