“Three years ago, when the Irish beat the All Blacks for the first time on home soil, they also delivered heavy blows to the tourists’ psyche by tackling themselves to a standstill and completely shutting down the slightest glimmer of light whenever it shone through the links in their defensive chain.

“This performance was better than their effort in 2018; the Irish wanted to attack, attack, attack by shifting the ball at speed from set phases, delivering quick passes in contact and it was no wonder that with 15 minutes still remaining that the All Blacks had already made more than 210 tackles.”

https://www.irishtimes.com/sport/rugby/international/view-from-the-new-zealand-press-final-whistle-was-almost-merciful-1.4728345

Those were the words of Richard Knowler, a columnist for stuff.co.nz, after New Zealand’s defeat by Ireland on their end of year tour in November. It was much, much worse for Wales in the first round of the 2022 Six Nations tournament. The men in red eventually lost by 29 points to 7 – but it could easily have been a 30, or even a 40-point margin.

Perhaps the most ironic aspect of Ireland’s success is that it is based around the ball-handling capacity of their forwards, which was superior to that of the All Blacks at the end of 2021. If you had said that about previous generations of Ireland forwards in comparison to their New Zealand counterparts, the comment would have been greeted by anything from muffled sniggering to outright laughter. The idea would have been plain absurd – but nobody is laughing now.

Ball-playing forwards are the oil in the Ireland attacking machine, they help open the width of the field and keep the momentum ticking over. Let’s look at some examples from the first half of the match against Wales.

One of the main problems for any team on attack is getting the ball out of a three-man pod of carrying forwards, and into to the backline with advantage. A lot of finesse is necessary in order to achieve this objective successfully:

This is Ireland playing confidently out of their own last third of the field with ball in hand. The key is the manner in which Ireland number 8 Jack Conan commits the three Welsh forwards opposite before releasing the pull-back pass to his outside-half Johnny Sexton:

https://ngm-blog-images.s3.us-west-2.amazonaws.com/Ire+pod+1.png!

When Sexton receives the ball from Conan, he is already on the outside shoulder of the last Welsh forward (number 2 Ryan Elias). That in turn means that Elias has to run laterally to stay in touch with him, and it commits every defender outside him to running in the same direction – straight towards the far side-line. Ireland have attained the width they seek through excellent basic technique in their forward passing.

The same pattern was repeated on a number of occasions during the first period:

In this instance the ball-carrier in the middle of the pod is number 6 Caelan Doris, but the outcome is very similar:

https://ngm-blog-images.s3.us-west-2.amazonaws.com/Ire+pod+2.png!

The delay on the pull-back pass ensures that the last Wales forward (number 7 Taine Basham) and the first back (number 13 Josh Adams) have to push off towards the side-line rather than move forward and deliver pressure on Sexton. The final defender (left wing Johnny McNicholl) has to turn a complete 360-degree circle in order to get back on terms with Conan in the wide right channel.

Perhaps the most lucid example was provided on a carry by the Ireland tight-head prop Tadhg Furlong:

Furlong takes the ball so far into the teeth of the defence before releasing the most delicate of pull-backs, that there is no chance for the Welsh defenders opposite him to recover and move on to the outside-half:

https://ngm-blog-images.s3.us-west-2.amazonaws.com/Ire+pod+3.png!

Wales scrum-half Tomos Williams finds himself buried in the grasp of the outside man of the Irish forward pod because the delivery is so late, and Adams is committed to the threat of Garry Ringrose further outside. That gives Johnny Sexton a nice big hole to run through and create the opportunity further out.

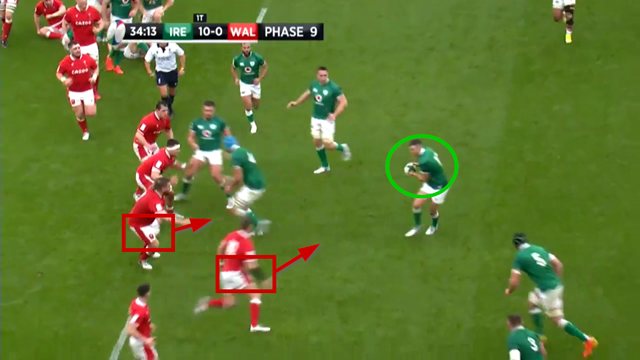

Later in the half, Wales tried to bring their first back outside the forward pod in tighter, to rush Sexton before he had the chance to enjoy the space around the end of the three-man unit:

https://ngm-blog-images.s3.us-west-2.amazonaws.com/Ire+pod+4.png!

The pass out of the middle of the pod by hooker Ronan Kelleher is less effective, which leaves the last Welsh forward (Tomas Francis) free to move forward, and Dan Biggar free to blitz up on Sexton after he receives the ball:

The veteran Ireland number 10 still finds a way to make the play work, dipping inside Biggar before a terrific underarm offload by Hugo Keenan exploits the space down the left-hand side.

Summary

The world has indeed turned on its head from the amateur era. Back in the day, the Ireland forwards tended to known more as rough-housers and spoilers, rather than as deft handlers of the ball. Now, they are the ones creating space in which their backs can flourish. Their handling and timing of the pass out of a three-man pod is truly exemplary, and defines the positive connection between forwards and backs in the current Six Nations.

.jpg)